earth, wind, water and fire: climate change has long since come to Cedar Rapids

A month after a derecho with winds equivalent to a Category 4 hurricane hit Cedar Rapids, the time is out of joint. Decaying tree debris piles look like fresh-raked leaves in autumn. But it is not autumn, not yet. Look above, where leaves in the ragged tree canopy are still green. It’s still summer.

“The tree rings are doomsday clocks,” I keep thinking, as we drive past piles of logs spreading into the roads.

tick tick tick goes the Carbon-14

Elements are supposed to be eternal; neither fire nor millstone nor flood can destroy them. But Carbon-14 is not an element; it is a stopwatch. Unlike the other two natural isotopes of carbon—Carbon-12 and Carbon-13—Carbon-14 is radioactive. It has a half life. The time it takes for half of it to rot: 5,700 years.

Carbon-14 does for time what God did for humankind: it gives it a body.

Carbon marries diatomic oxygen, and the two elements become one molecule, one body: carbon dioxide. From there, plants photosynthesize it into the fibers of their being. Animals eat the plants, and carbon forges its way into animal tissues and bones. Most of that carbon will be Carbon-12, but some of it—just enough to detect with radiometric tests—will be Carbon-14.

Inside all living things, the proportion of Carbon-14 to Carbon-12 calibrates to the ratio in the air.

This ratio remains in equilibrium as long as plants photosynthesize and animals eat, but the moment roots get yanked from the soil or a heart stops its thump, thump, thump, Carbon-14 begins to decay, while Carbon-12 lives on.

Time does not end at death: it begins.

Plants exposed to fossil fuel pollution are natural forgeries, dating much older than their actual age: calibrated to the air of long-dead things on fire, depleted of carbon-14. The Seuss Effect, it is called, after Hans Seuss. But we can correct for it: Inside the trees, the rings record carbon ratios year after year, a standing account of anthropogenic effects, a scroll of all our human sins against nature.

Fossil fuels compete with the Bomb, which flooded the world with Carbon-14. Yank a tooth out of a post-bomb body, and you can calculate a corpse’s birth date within 1.5 years. Teeth stop forming at an early age, so they stop picking up carbon, and because they erupt through the gums in predictable patterns, the mouth is like a timeline of exposure to Carbon-14.

But it only works for people born after 1960. For people born in the 50s, it gets tricky because their dentition formed during a time of great flux in radiocarbon levels: BOOM, C14 up and down, up and down. Tooth 18, which erupts after Tooth 19 might wind up with a lower radiocarbon content, even though it’s younger.

The Bomb Effect.

When I lived in Utah, I thought of the Bomb Effect and the Seuss Effect as the war between Time and No Time and Utah was the battlefield. From Downwinders to oil refineries & tar sands.

Everywhere is the battlefield. Climate change is the bomb.

The trees are dead. We wound their doomsday clocks.

tick tick tick

By the time the sirens went off on the day of the derecho, it was too late to prepare.

My husband and I watched from our windows as wind stripped branches off a walnut tree, easy as blowing a dandelion poof. I cried as our recycle bin rolled toward my baby rose bushes and stomped out the blooms like an AT-AT. A neighbor’s tree collapsed and smashed through the roof of a garage. Another neighbor’s siding and shingles flew off like Frisbies. Our wooden fence posts snapped.

“That’s not a tornado sky,” I said, trying to make sense of it. But the wind whistled like one, that familiar freight-train-rolling-right-over-you sound we all know means take cover. We never imagined a hurricane. Iowa doesn’t get hurricanes.

Forty minutes later, when the winds died down, the neighborhood emerged from our front doors — no masks, no social distancing — into new alien terrain. All our beloved old growth trees were gone.

“A tornado touched down on our street in the 70’s,” a neighbor told me, “and it was nothing compared to this.”

Later, when our street was clear, we ventured out to see the rest of the city. All over town, this was the scene:

At Oak Hill Cemetery, a tree that has stood since at least 1912 when Walter Douglas died aboard the Titanic got knocked over by the root ball:

Near Bever Park:

I didn’t know trees could do that.

The force was so strong it flipped the sidewalk over with it, blocking the path of disabled people & seniors: Look at the force! It bent the rebar in the concrete as easy as flipping a page in a spiral notebook.

As an epileptic who cannot drive, who pops rollator wheelies over busted-up sidewalk slabs and curbs with no curb cuts, it hurts to see sidewalks destroyed. I grew up here, an epileptic kid in Car City, city of missing sidewalks, city of buses that don’t run past sundown, city of no buses on Sundays. I walked the shoulders of busy roads. I walked the railroad tracks alone in the dark. Cedar Rapids was so inaccessible that in 2015, the Department of Justice warned: Comply with the Americans with Disabilities Act–or else.

Complete Streets, the city called their new sidewalk plan, confessing they had not been complete before. And yet, in the criteria, “neighborhood acceptance”:

May 27, 2016, Cedar Rapids Gazette:

“I don’t like sidewalks,” 94-year-old Ida Pratt said. “We don’t need them. Nobody even walks here.”

Nobody even walks here.

I used to get angry at the “STOP SIDEWALKS/SAVE OUR TREES” signs. Were disabled people worth less than trees? Now, I am not sure what to make of them.

After derecho, a man walked up while I was taking photos and asked if I was publishing them. I told him about The Log Project my husband and I are doing, collecting logs from places of personal or historical significance to saw slabs & create a wooden codex, like an ancient book.

“We knew that tree was going to fall,” he said, pointing at the rootball that flipped a whole sidewalk slab. “It was only a matter of time. When the city put the sidewalk in, they cut up the roots, made it weak. Another one just like it toppled in a snowstorm. This one fell so easy, it didn’t even make a sound.”

He looked sad, maybe resigned, and I realized the protest signs — at least some of them — were sincere. I had always believed the slogan fake, cooked up to make anti-sidewalkers look like environmentalists.

But did the sidewalk kill the trees or the storm?

“I got a log from my childhood home in Hiawatha. A tree I used to climb.” You would never know she was born with a broken hip, my father used to say. She can climb right over the tops of trees.

“Where in Hiawatha? I was a postman for 20 years and it was on my route.”

I told him the street.

“What name?”

“Higgins.”

He rattled off the address without pause, even though my parents moved seventeen years ago.

Then he rattled off the addresses of everyone else on the street who is still there.

We are all connected.

But without the sidewalk, how do we connect?

Evidence of my use. Tracked like some wild thing.

What evidence would I leave now? I cannot walk on uneven ground.

If an epileptic walks on the shoulder and nobody sees them, is there still evidence of pedestrian use?

Missing sidewalks, in red:

Car People think people like me are a Russian plot:

City Council Meeting June 2017, resident Joe Day:

We don’t walk down the street. We drive.

It has no purpose whatsoever, other than Russian logic that because we (did road work on) Bever Avenue, ‘Ve vill have sidewalks whether you like it or not.’ [mocking a Russian accent] “Well, we don’t like it. It has no purpose.

Sidewalks voted down.

Then-Mayor Ron Corbett:

…[W]e can’t treat policies as if they are the Ten Commandments written in stone coming down from the mountaintop.

And yet, people are treating the derecho as an act of God, as if we didn’t blow our own houses down with climate change.

The city is piling up the felled trees in Time Check, a working-class & poor neighborhood that got decimated in another climate change disaster: the 2008 flood.

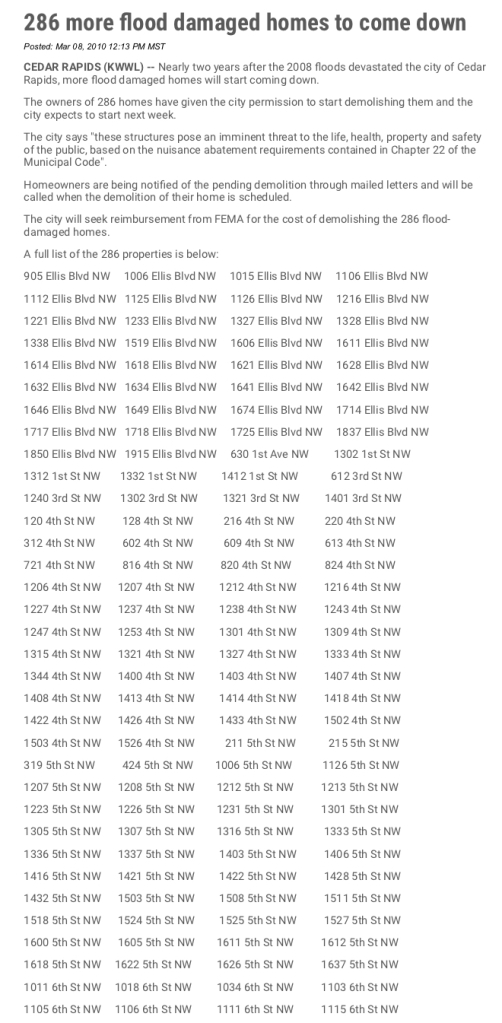

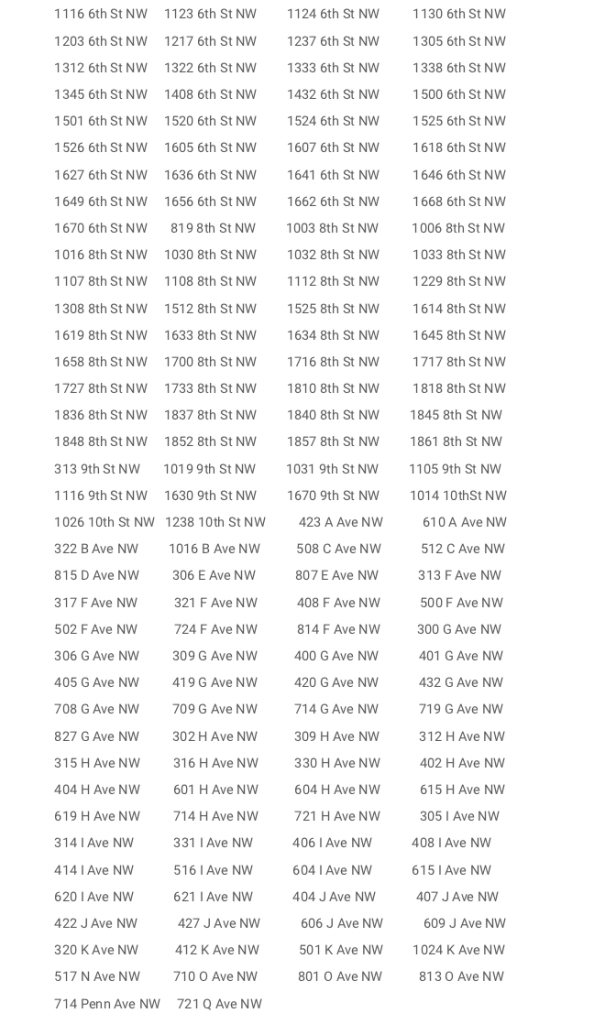

Home after home, declared uninhabitable and demolished:

One of those houses on G Avenue: my mother’s childhood home. When we visited in 2011, she led us to the lot where it used to stand. She pointed to all the other empty lots where people she loved used to live. After derecho, I got a log from a tree her twin brother used to climb to sneak onto the rooftop.

One of those houses on G Avenue: my mother’s childhood home. When we visited in 2011, she led us to the lot where it used to stand. She pointed to all the other empty lots where people she loved used to live. After derecho, I got a log from a tree her twin brother used to climb to sneak onto the rooftop.

In 2018, for the ten-year anniversary, the city erected the West Side Rising flood memorial, featuring steel silhouettes of ghost houses, representing all the lost homes in Time Check. Some stand tall, some are tipped as if flowing away in a current. Atop the tallest houses: blue clocks, a nod to the blue porch lights neighbors lit to signify, “I’m still here.”

Except instead of porch lights they are clocks, permanently set to 10:15, the moment the river crested on June 13, 2008 and washed the neighborhood away: tick tick tick—-the end of time

The neighborhood is never coming back. It’s a designated flood plain now: the memorial will go under again and again and again, the Cedar River flowing through the open houses.

Derecho blew an evergreen right through one of the houses. Two disasters, intersecting.

It came up by the rootball, too: uprooted, like the people of Time Check:

Westside Rising Flood memorial, pictured in 2020 after derecho. Steel outlines of houses, with a few tipped over, and the two tallest ones have blue clocks set to 10:15. Most of the trees are gone, and the evergreen from the previous photo has fallen and crashed through one of the tipped over house sillhouettes.

Time Check, so named because railroads paid workers with post-dated checks that banks cashed on credit. The neighborhood lived on borrowed time.

After the 2008 flood, city officials started brainstorming ways to avoid another traffic nightmare. — Dora Miller, Channel 2 Cedar Rapids

During the 2008 floods, I-380 was the only option. Newspaper photos look apocalyptic: a city with a flooded coal-fired electrical plant, no electricity, no lights, all its bridges underwater; Mays Island on which City Hall and the Linn County Jail float, abandoned, drowned, not one human to be found; towers rising out of the dark waters, windows inscrutable.

This is the way the world ends, not with a bomb, but a flood.

And yet, cloaked in that darkness: cars creeping across the I-380 bridges, their headlights the only illumination. 15,000 cars a day cross the 8th Avenue bridge alone: raise it ten feet, and it will be like God never sent the floods at all.

“Downtown is going to be operating as normal versus in 2008 you know it was closed so we need that transportation element preserved,” said Richard Davis, Cedar Rapids Flood Control Manager.

Bridge as Tower of Babel.

Even as ADM loads coal into its burners to process the corn to make the ethanol that quickens global warming. The same coal banned from Prairie Creek Generating Station starting 2025.

We can’t treat policies as if they are the Ten Commandments.

This is the end of the road. We have to pick a direction. What will it be?

One day, while my spouse was out filming trucks hauling tree debris into Time Check, a woman whose house survived the flood came out to ask if he was one of the workers. “No,” he said, explaining how we are artists documenting the storm.

She told him how the workers kept dumping logs in her yard and knocking down her electrical line, how her little girl used to swing in the tree that uprooted and fell in her own yard. “Everybody called us The House With the Girl in the Swing.” Now there is no tree to swing on and no neighbors to see it. Just a sea of logs and branches and wood chips in the empty lots where all her friends and neighbors used to light their porches.

“Why don’t they dump them out in Czech Village where there aren’t any houses?” She said. “Everybody else gets to heal, but not us.”

The other night, when a blood red sun set behind the piles of debris on our street, I thought about how smoke from the fires out west where I used to live had given us this apocalyptic scene. Two disasters intersecting again.

The time is out of joint.

When trees burn, old tetraethyl lead emissions seep out. The trees become cars.

In 2010, Kinglsey O. Odigie and A. Ruddell Flegal leached lead from ashes of 2009 Jesusita Fire in Santa Barbara County, California, using nitric acid. Lead inside the ash “ranged from 4.3 to 51” micrograms per gram. They mapped the isotopic ratios down to fractions of degrees of latitude and longitude and dated them based on tetraethyl sources and the industrial history of the area.

Lead contains a kind of DNA: its isotopic composition, the ratio of 206Pb to 207Pb. You can trace it to the parent soil, like a genetic genealogist:

- Australia: 1.037

- Canada: 1.064

- Mexico: 1.192

- Peru: 1.2

- Missouri: 1.28-1.33

In the 1960s, the United States imported lead ores from Australia, Canada, Mexico, and Peru, and the lead deposits in the Santa Barbara Basin reflect that timeline. In 1976, production bumped up in Missouri, and there it is in the fire ash, too: the trees are keeping records. We are not getting out of this.

We are breathing the air of long-dead cars on fire, and so are the trees. How jumbled will the timelines be inside the tree rings of 2020?

This week, our smoky air tasted like the pollution in Salt Lake City, when inversions would trap emissions from oil refineries, cars, mining, and medical waste incineration in the valley for weeks or months:

When I lived in Utah, I used to post screen grabs of the Air Quality Index every day to Facebook. “You’re exaggerating,” people used to comment.

Or: “Why don’t you just leave?”

Now, my social media feed is flooded with screen grabs of AQI.

We are all canaries in the coal mine. We are all connected.

Air flowing clockwise around high-pressure systems pressing down on the Great Basin — my beloved Utah — give birth to the Santa Ana Winds that fan the flames of wildfires in California. Clockwise, trying to set time right.

All canaries. All connected.

As I watched the red sun set in the sky, I remembered a man sitting on his porch in Time Check next to Westside Rising, how he said he survived by the grace of good flood insurance back then. He was able to rebuild.

He didn’t want to leave Time Check, just like I didn’t want to leave Salt Lake City.

But now, surrounded by that sea of tree debris? “If someone tosses a cigarette and lights it on fire,” he said. “No fireman is coming.”