Visual representations of climate scenes have not been perceived as immediately comprehensible or compelling evidence of climate change, failing to provoke strong emotional reactions in audiences. By contrast, a violent crime scene, whether in fiction or real life, can lay bare the very things a community might be trying to conceal, including racism, sexism or class inequalities, while rousing an immediate passionate response to the incident. Unlike climate change communication, representations of crime scenes have been affective, visual entry points into ordinary people’s understanding and imagination of crime. By making concrete the abstraction of crime, the visceral impact of mediated crime scenes has compelled politicians and citizens to transform local incidents into pressing catalysts for criminal justice policymaking. Given its enduring popularity, the visual vocabulary for representing crime can be fruitfully borrowed by climate change communicators, especially in light of their crisis in representation. Thus, by reading climate scenes as though they were violent crime scenes, we bring the criminological imagination to bear on an area of media communication that has been less effective at depicting the environmental harms that potentially threaten us all.

—Criminal Anthroposcenes: Media and Crime in the Vanishing Arctic by Anita Lam and Matthew Tegelberg

Last winter, when I visited the tree dump site in Time Check — where the City of Cedar Rapids piled felled & damaged trees from derecho & processed them into mulch — I felt like I stepped into a dream of midwestern mountains.

An early morning chill evaporated water inside the fresh wood chips, steam rising from the piles like miniature Smoky Mountains–a geographic forgery this city has attempted before.

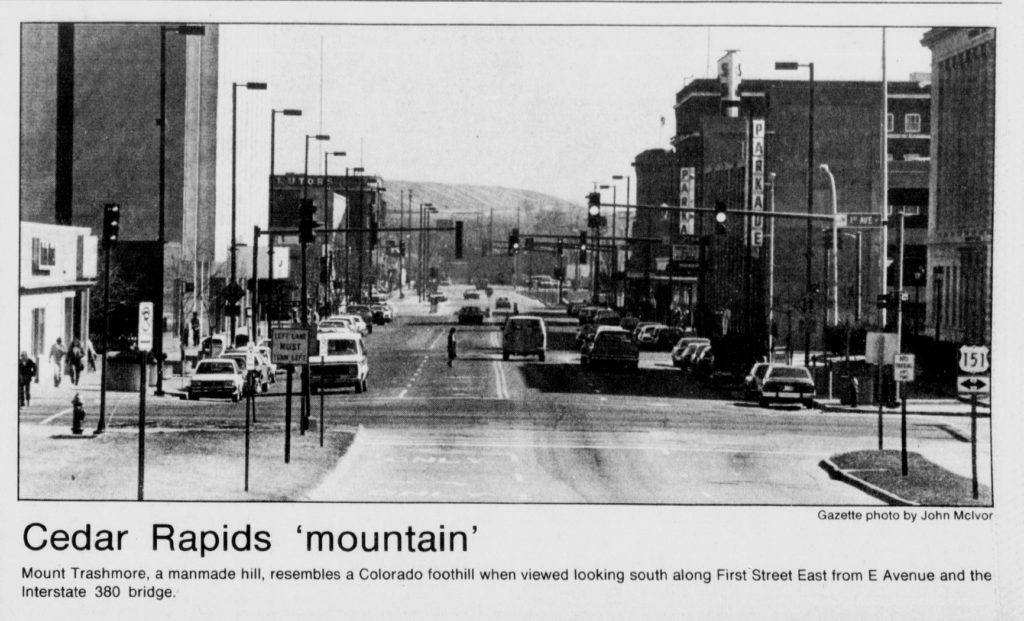

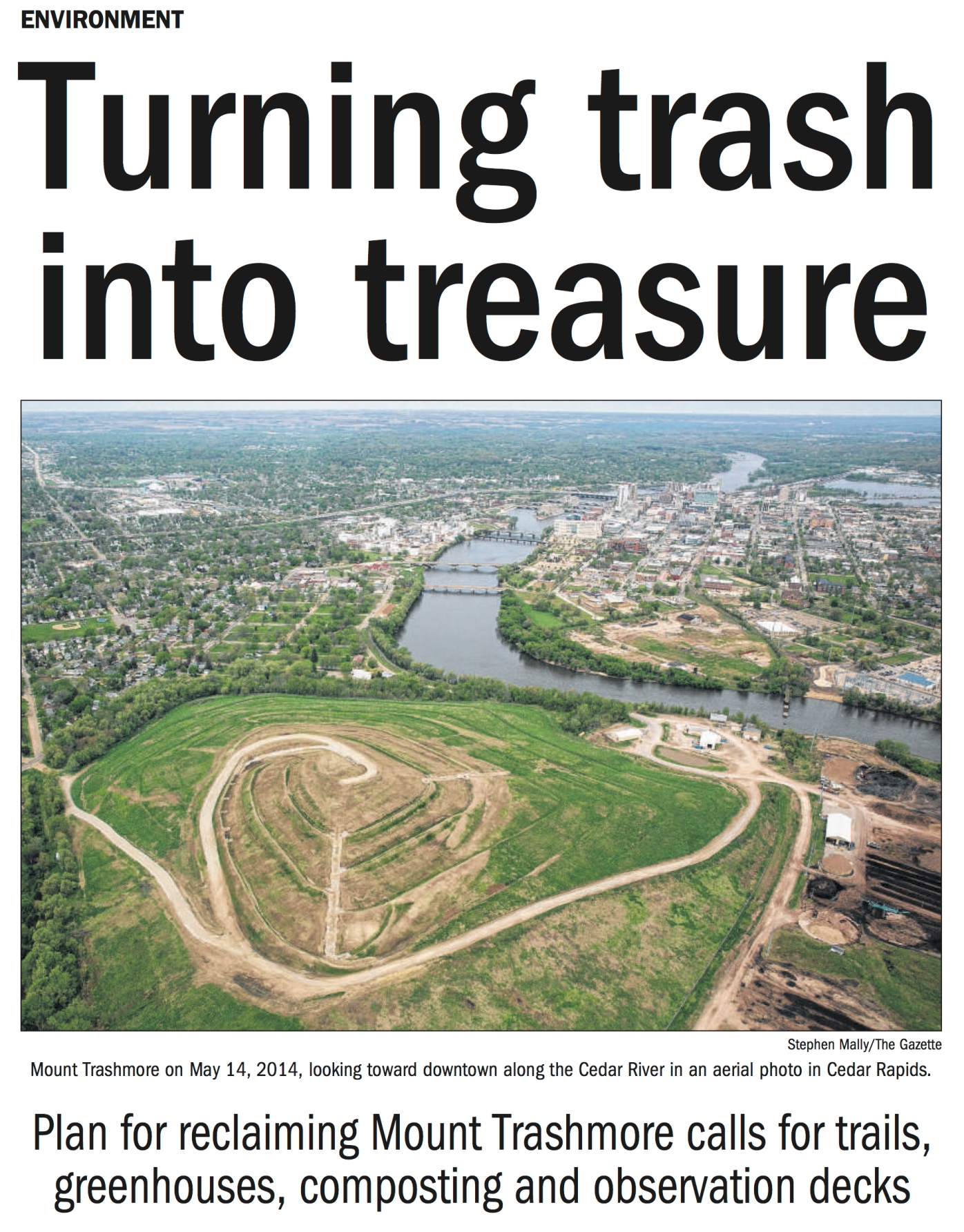

Mt. Trashmore, city dump, our manmade “Colorado foothill”:

When I walked behind the piles, I discovered a clearing filled with idle tractors and a strange shelter that resembled an arctic research outpost.

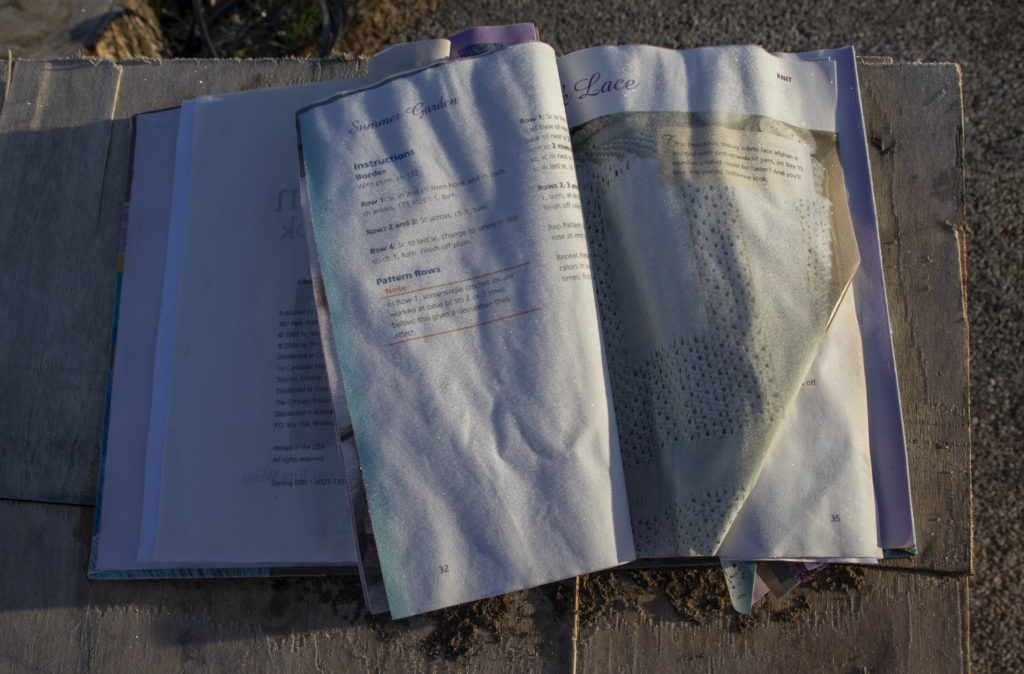

And beside that tower, atop the crate, this book:

Next to it, I found a teddy bear strapped to a tree trunk:

Its fur was coated in a fine layer of frost, and it looked like it had weathered sun & rain for weeks or longer. The tree trunk had been spray painted with the dreaded “x,” meaning the city had doomed it to the chainsaw.

Of all my derecho photos I shared on social media, this was the one that got to people. One person said it gave them nightmares. Another said it made them cry. Not trees toppled over by the root balls. Not tombstones in Oak Hill Cemetery knocked off their bases by flying debris. Not cars smashed flat under walnut trunks.

A teddy bear.

I can’t help but think it was because it’s a bear.

In Criminal Anthroposcenes: Media and Crime in the Vanishing Arctic, Anita Lam and Matthew Tegelberg cast polar bears as the perfect climate change victims: fluffy, white, cute, threatened, and photogenic. But their whiteness — symbol of purity and innocence, just like the racist construction — is an illusion. It’s “created by a process known as luminescence, which occurs when light energy from the sun’s rays gets trapped within the hollow surface of the polar bear’s fur. This trapped light energy causes polar bear fur to appear white.” As the permafrost melts, exposed soil and foliage reflect warmer tones onto polar bears’ fur, and suddenly they appear sallow. On instagram, they become #SickBears.

But the bear is not just “sick,” it has been sickened by an environment that humans have made sick. #SickBears are murder victims & photos of them wandering a thawing arctic are crime scenes.

My teddy bear photo evoked all those images of lonely, hungry polar bears wandering the thawing arctic. But unlike the #SickBears, the tie around its neck pointed directly to human violence. It was, as Lam & Tegelberg call it an “anthroposcene.”

Indeed, a branch of criminology exists for crimes against the environment & environmental justice. And while the derecho itself could not be called a “criminal” — though it felt like an evil force attacking our state, it of course was not sentient — the climate change that is shifting derechos poleward most definitely is:

This is because the bands of fast upper-level winds that arise from the equator-to-pole temperature gradient — the jet stream — would contract poleward in a warmer world. Because derechos tend to form on the equatorward side of jet streams, especially those that mark the northern fringes of warm high-pressure (“fair weather”) systems, the areas most favored for derecho development also would shift poleward. It is unclear, however, how jet stream changes might impact derechos from a wind shear perspective.

What was there is now here.

But it was always here, in our jurisdiction, and we never prosecuted the crime. Now we have come full circle: a wave of mulch crashing into the memorial to the high water mark of the Flood of ’08, where the wave of the Cedar River spilling over its banks took out almost the entire Time Check neighborhood:

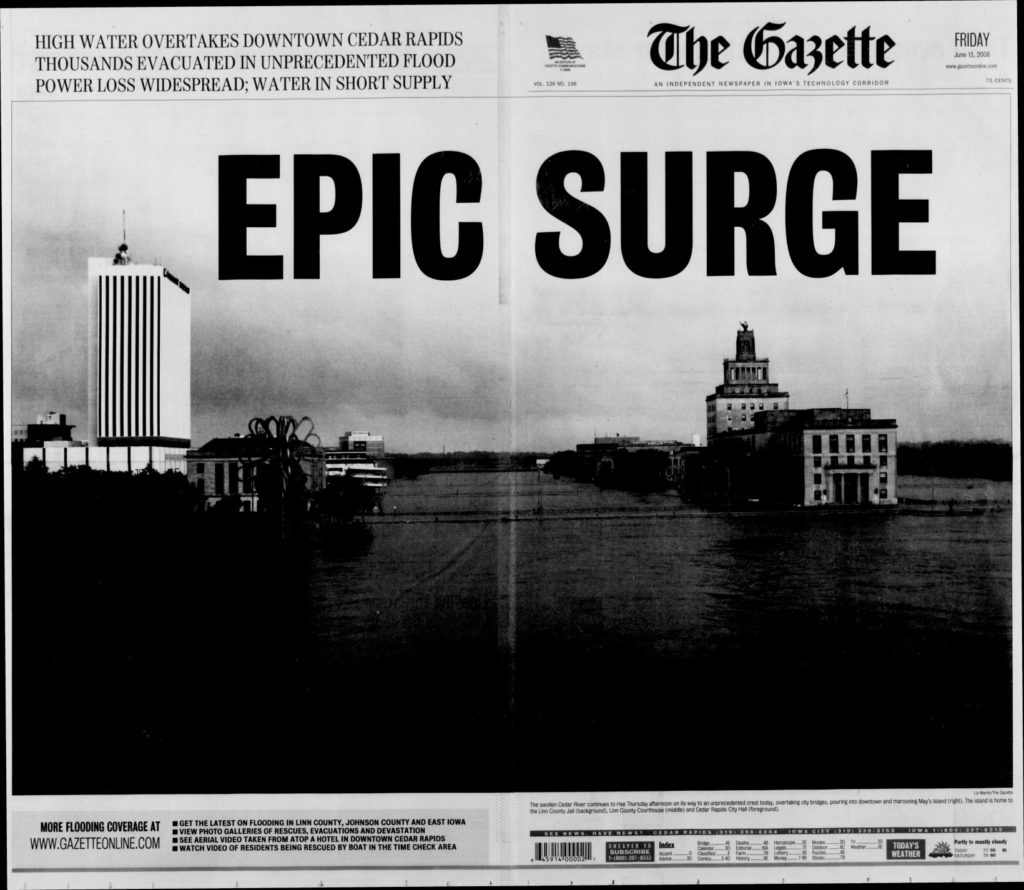

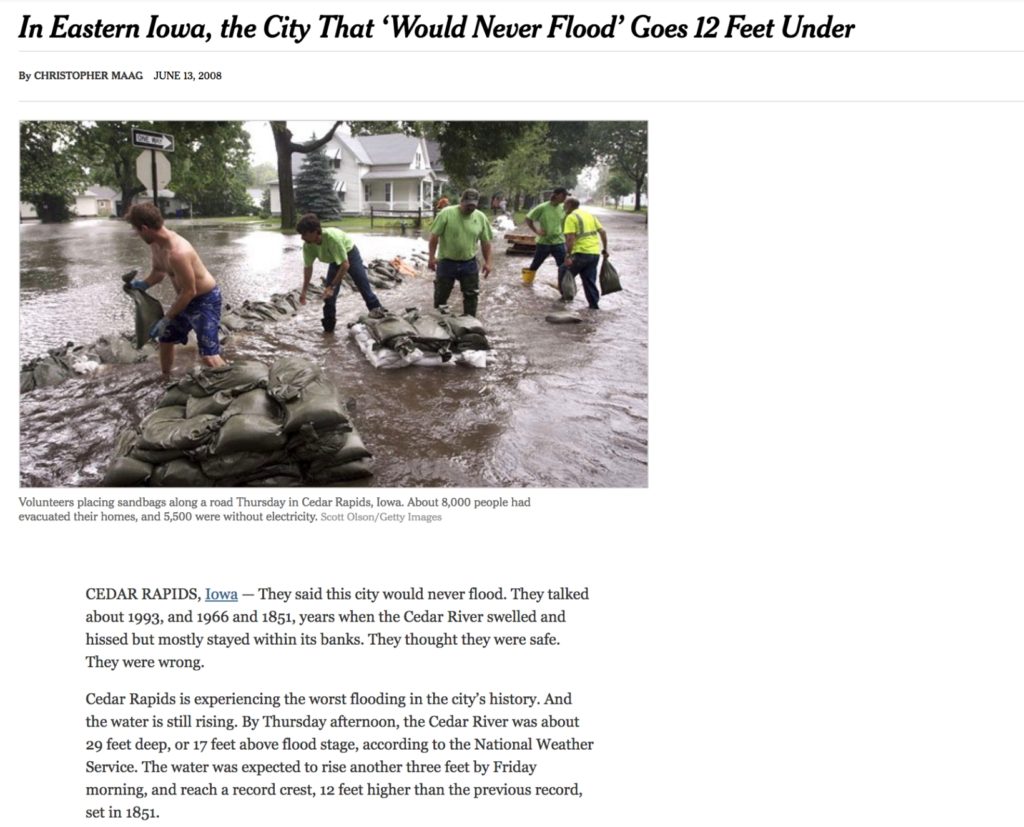

Cedar Rapids Gazette, June 13, 2008, the day the Cedar River crested and drowned 1,126 city blocks:

I watched from afar in Portland, Oregon, as all my childhood landmarks went under.

The World Theater, where I shuffled my feet on the gum-spotted sidewalk under the marquee and pretended I lived in a real city, somewhere far away in the west: laid to rubble.

photo credit: http://cinematreasures.org/theaters/7147/photos/192860

photo credit: http://cinematreasures.org/theaters/7147/photos/192858

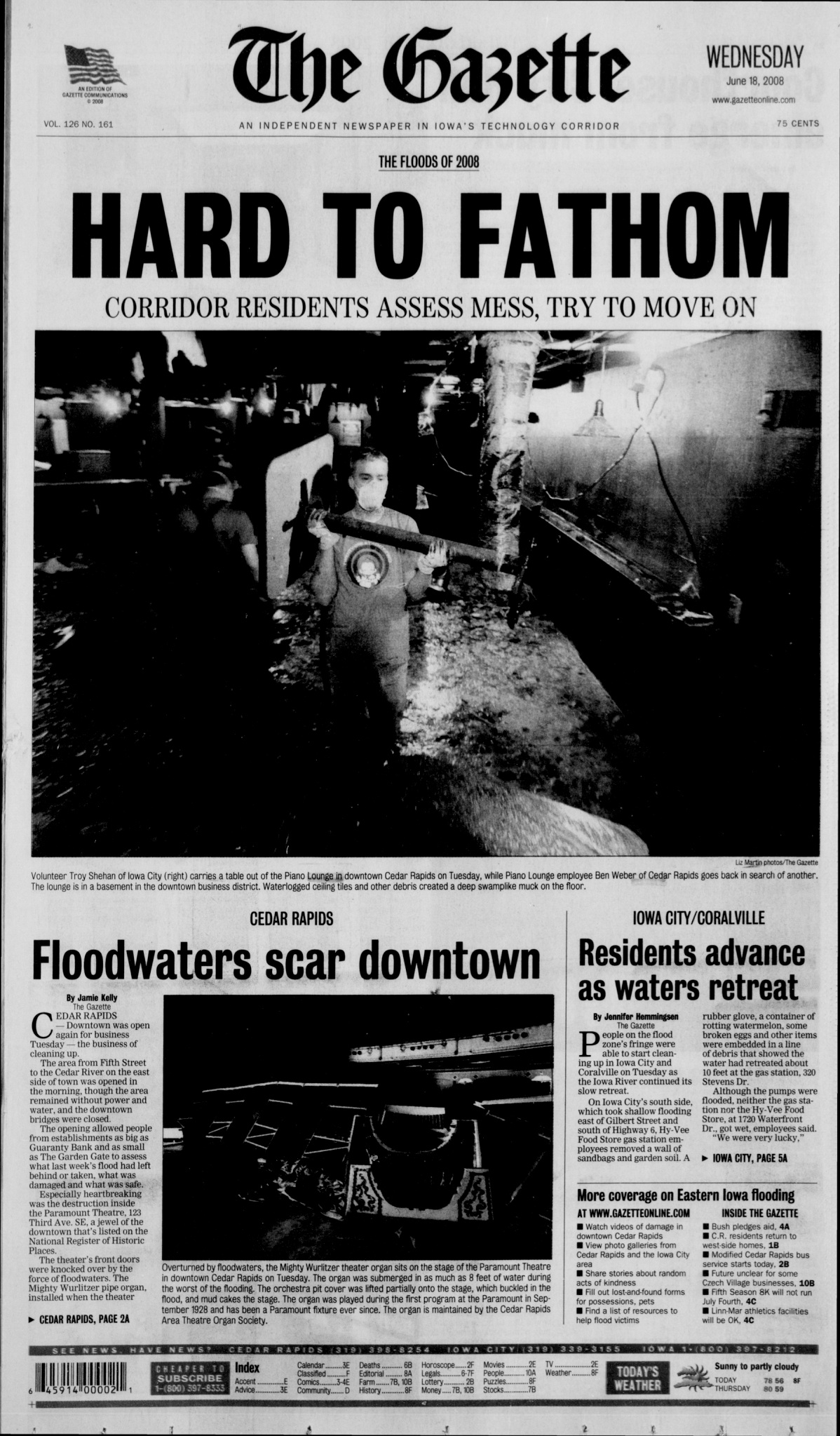

The Paramount, where I tap-danced and pirouetted on stage: doors thrust off their hinges, currents roaring into the auditorium, knocking over its Mighty Wurlitzer like a bowling pin.

I imagined floodwater rushing all the way to the proscenium, its red velvet curtains at first billowing outward, floating like Ophelia’s petticoats, until they saturated and sank, dragged down by their own weight.

“We’re just kind of at God’s mercy right now,” said Linn County Sheriff Don Zeller, “so hopefully people that never prayed before this, it might be a good time to start.”

In the New York Times, this headline:

The City That Would Never Flood. Nobody in Cedar Rapids had ever called our city unsinkable as far as I knew, and yet, we behaved like we believed it.

Even after the flood of 1993: river crest, 19.27 feet. I was newly 18, newly graduated, preparing to move out. I worked at a little shop in Westdale Mall engraving jewelry. One night: flash flood warnings. I could not drive, could not flee work. My mother and aunt rescued me in Aunt Joann’s little green Ford, and she hit the pedal to the medal to beat the water as it rushed around us, trash bins floating by on the current.

When her car stalled, she prayed to God: Start little car, start little car, start little car, and it did. We fled to her apartment tower, right on the river’s edge, rode the elevator to the tippy top, and she said, “We are at God’s mercy.”

The city did not build a flood wall after ’93. We never changed our ways. A fluke of the weather, nothing more, we thought.

We forgot our own history, how the centerpiece of our city got built: May’s Island, home to the courthouse, to the Veterans Memorial Building, to the jail:

May’s Island is May’s Island because of a flood:

While most viewed the island as useless, May saw potential on the roughly four-acre landmass.

As soon as the island was platted into 62 lots, May began an extensive marketing campaign to entice businesses and residents to his island. At one point, May even had a roller coaster constructed on his island in an attempt to increase foot traffic.

But while a few buildings began to pop up, the wooden bridges built to provide access regularly were washed away by floodwater.

But things were about to change.

A bridge, a furniture store

Nearly two decades after the island’s platting, floods caused the city’s First Avenue Bridge to collapse, leaving the recently completed Third Avenue Bridge as the only means of crossing the Cedar River in the downtown area.

“All of a sudden he’s got a permanent, stable bridge not only crossing the Cedar River, but crossing the Cedar River right in the middle of his island,” Stoffer Hunter said.

A new First Avenue Bridge wasn’t completed until 13 years later, which left the bridge across May’s Island as the primary crossing point for the city for more than a decade.

We made May’s Island into a midwestern Titanic.

A civic center

As the city’s population grew rapidly in the 1890s, Cedar Rapids officials began eying May’s Island as an opportunity to create a center for government services and events.

But flooding remained a primary concern, so the city first needed to elevate May’s Island. Thousands of tons of dirt were trucked in to build up the island, but also expand it north to reach the First Avenue Bridge.

Concrete flood walls were installed to shape the island, and the landmass grew to about nine acres. It was renamed Municipal Island.

As the flood walls went up to make May’s Island an unsinkable ship, a Cedar Rapids Captain of Industry went down on the ship that would never sink — the real Titanic.

Walter Douglas, son of a co-founder of Quaker Oats:

Founder of Midland Linseed Company, which went on to become Archer Daniels Midland.

ADM, the ethanol plant. Fuel for the cars that breathed the floods into being.

At the Douglas family tomb in Oak Hill Cemetery:

It felt like a message: a reminder of our history and how we got here. What has that tree seen? On which ring did Walter Douglas board Titanic? Contained in those rings: lead and mercury from the coal ADM burns to make the ethanol to fuel the cars, which exhale CO2 this tree used to absorb.

Even after ’93, never did we imagine the city would go under like it did in ’08: river crest, 31.12 feet. A 500-year-flood.

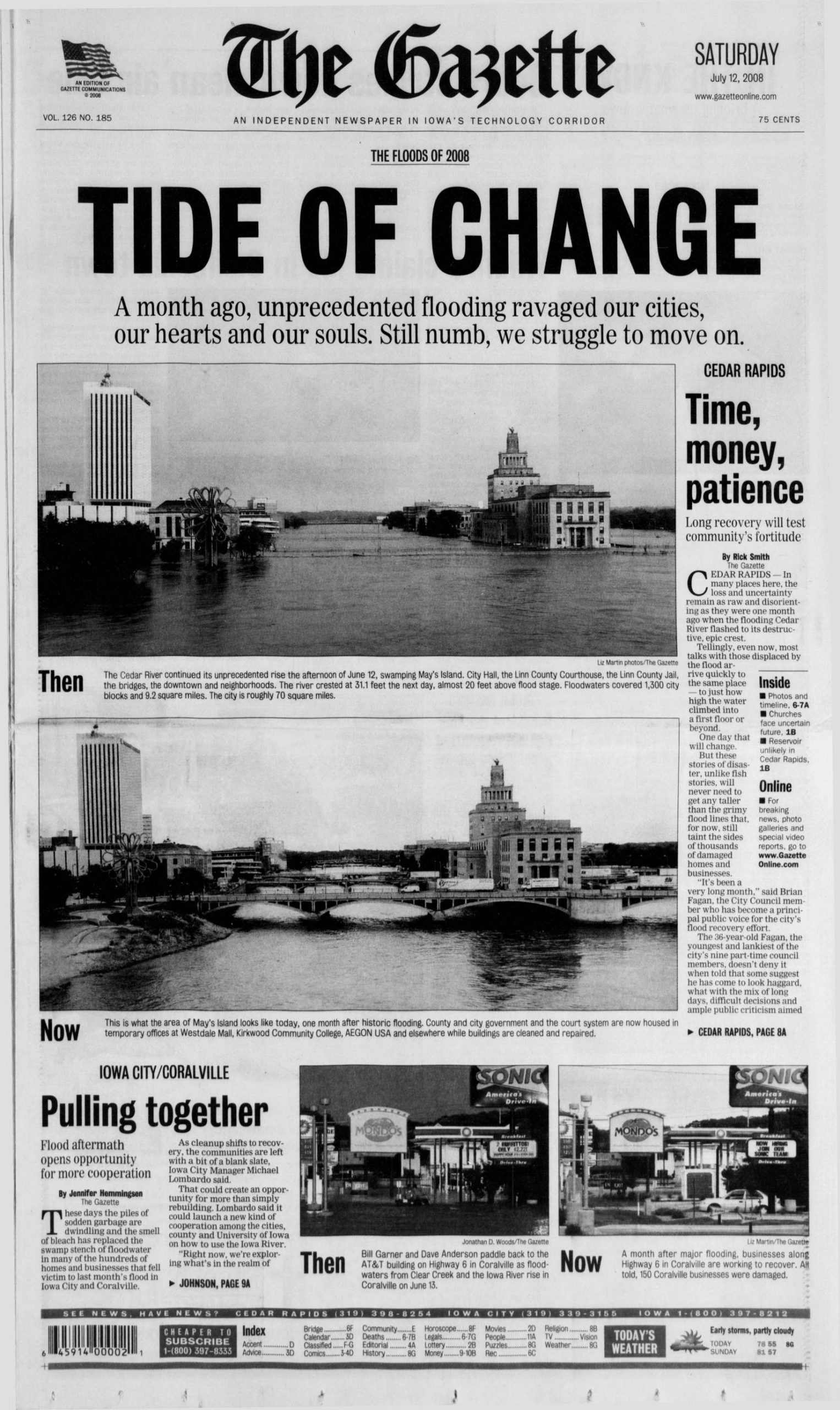

May’s Island became a real Titanic that day. Gazette, September 7, 2008:

In Time Check, so named because in the beginning, the railroads paid workers with post-dated checks that banks cashed on credit, water rose to the rooftops. The neighborhood was always living on borrowed time.

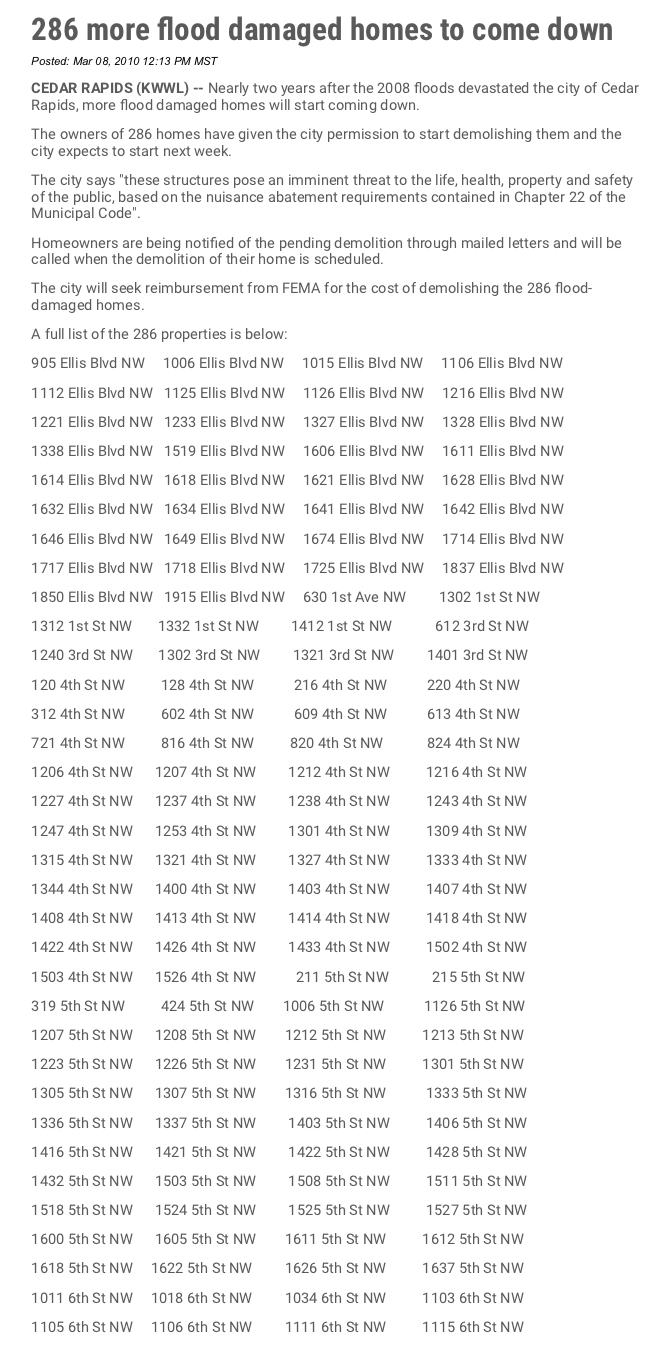

In 2010, the damaged homes got bulldozed:

Including my mother’s childhood home on G Avenue.

Residents planted white crosses on the empty lots, memorializing the houses like road-crash victims:

“I have to admit, at night (the crosses do) make the neighborhood look morbid. It looks a little like a graveyard,” Clemons said. “It doesn’t look good anyway!”

Karen Dlask, who lived in Time Check all her life and moved west to Johnson Avenue after the flood, took down four of the crosses – two at the site of her old home, and one each at two of her rental properties that were demolished.“To me, a white cross symbolizes death, human death. Not a property,” Dlask said. “Things are replaceable, people are not.”

But home is not replaceable, and the people are long gone. The white crosses made people uncomfortable because they demanded we look at the flood as a crime. At flora, fauna, and homes as victims.

It demanded we confront the social conditions for why a working-class neighborhood will never get a flood wall, never be rebuilt. The crosses demanded we see Time Check as an “anthroposcene.”

On some level, we knew we had to change.

July 2008:

But the flood wasn’t a tide of change. At least not the changes that would save us.

City Council Meeting June 2017, resident Joe Day:

We don’t walk down the street. We drive.

It has no purpose whatsoever, other than Russian logic that because we (did road work on) Bever Avenue, ‘Ve vill have sidewalks whether you like it or not.’ [mocking a Russian accent] “Well, we don’t like it. It has no purpose.

Do sidewalks kill the trees or do the cars?

Mayor Ron Corbett on the sidewalk plan:

…[W]e can’t treat policies as if they are the Ten Commandments written in stone coming down from the mountaintop.

After the floodwaters retreated in 2008, Mt. Trashmore – capped since 2006 – was unsealed to entomb 430,000 tons of debris. And now? It’s a real mountain.

Is this progress, or are we covering up our crimes?

Is this flood protection or denial?

River level forecasts have increased in Cedar Rapids, Iowa, since tropiclike rainstorms in 2008 caused the normally placid Cedar River to climb higher than anyone thought possible, eventually topping the previous record flood by 11 feet. More than 1,100 blocks in Iowa’s second-largest city wound up underwater.

Afterward, the Corps of Engineers raised Cedar Rapids’ projections for a 100-year flood by 8 percent. As part of a massive flood-control project, the city decided to raise its Eighth Avenue Bridge by 14 feet, putting it 28 feet above the average water surface.

“What used to be the norm is no longer the norm,” said Rob Davis, the city’s flood-control program manager. “The norm is much higher.”

During the Flood of ’08, every bridge over the Cedar River in downtown Cedar Rapids went under except I-380. The cars drowned their own bridges. Raising the 8th Avenue bridge ensures east-west access in case of emergency, but it also means: we have accepted disaster as our norm.

Or: We can defy the natural consequences of our actions. Defy nature itself.

Bridge as Tower of Babel.

In Time Check, the memorial to the flood got pierced by a tree felled in derecho, as if to say: if not water, then wind. You are not getting out of this.

“We don’t need a reminder! All we have to do is look out our windows and see there’s no houses anymore,” one resident said when the memorial went up.

But the sculpture doesn’t just memorialize the houses; it memorializes the crime.

At the top: clock faces representing the blue porch lights residents flipped on in the wake of the flood, signifying: I am home. I am not leaving. The time is set permanently to 10:15, the moment the river crested on June 13, 2008 and washed the neighborhood away: tick tick ti—-the end of time.

In July 2018, Cedar Rapids finally secured federal funding for a permanent flood protection system after 10 years of fighting. The Army Corps of Engineers had said: we don’t see a return on investment here. The country wants cheap ethanol, but they don’t care what happens to the people in the shadow of the ADM plant that burns coal to make the ethanol they sell you as “clean,” even though it fuels climate change.

The memorial will go under again and again and again. I imagine water rushing through the steel frames all the way to the roofs, until the end of time. Every disaster a re-enactment of the crime that erased the houses, the neighborhood.

In summer, I returned to Time Check to look for the teddy bear. I hoped to find out the story behind it, but it was gone. The tree it was strapped to was gone. The arctic outpost was gone. The field where the mountains of mulch once stood was empty again.

This crime scene has been all cleaned up, the evidence long since trucked away.

And yet, if you knew what this neighborhood once was, the empty lots are evidence, too. You don’t need a #SickBear to know a crime has been committed here.